This article is based on concepts from Collier’s Guide to Night Photography. Our readers can get a discount by using the promo code picturecorrect at checkout.

Of all the phenomena you can view in the night sky, the northern lights may be the most spectacular. These lights, which are also known as the aurora borealis, are created by charged particles from the sun interacting with gaseous particles in our atmosphere. They also appear in the southern hemisphere, where they are known as the southern lights or aurora australis.

Brooks Range, Alaska, 14mm, f/2.8, 10 seconds, ISO 6400. (Photo by Grant Collier)

Finding the Northern Lights

You can view a forecast for the northern lights at the University of Alaska’s website. This website gives you a general idea of where the northern lights will be visible on any given night. For example, if you are in the northern continental United States, you might be able to see the northern lights if the forecast is rated five or higher. However, to get the best chance of viewing the northern lights, you’ll need to travel even farther north. To discover the best locations, try to find a day when the University of Alaska predicts a forecast of one or two.

Looking at their map, know that anywhere within the bright green circle is a prime viewing spot for the northern lights. Some places that are somewhat easier to access in prime viewing areas are Dawson City and Yellowknife in Canada; Wiseman, Alaska; Iceland and northern Norway.

Jokulsarlon Lagoon, Iceland, Nikon D800e, 18mm, f/2.8, 20 seconds, ISO 3200. (Photo by Grant Collier)

What Lens to Use

When shooting the northern lights, it is very helpful to use a fast, ultra-wide-angle lens that has an aperture of f/2.8 or wider. These lenses can let more light into the camera, which will yield higher quality images at night. Perhaps the best lens for shooting the northern lights is the Sigma 14mm f/1.8 Art. This lens has the widest aperture of any 14mm lens, and the Sigma Art lenses are always of very high quality. However, it is quite expensive, with a retail price of around $1,400. A lower-cost option is the Rokinon 14mm f/2.8, which costs around $300. If you prefer a zoom lens, the Tamron 15-30 f/2.8 and Sigma 14-24mm f/2.8 are both very good options.

Wiseman, Alaska, 14mm, f/2.8, 15 seconds, ISO 6400. (Photo by Grant Collier)

Camera Settings

You’ll typically need to use the widest aperture on your lens, and I recommend a shutter speed between 10 and 15 seconds. If the lights are moving rapidly in the sky, they can start to blur too much with longer exposures. If the northern lights aren’t moving rapidly, you can get away with exposures of 20 to 30 seconds with a wide-angle lens.

Generally, an ISO of 1600 will work well for shooting the northern lights. I recommend underexposing the images a little so that you won’t risk blowing out the highlights if the lights suddenly brighten. You’ll want to frequently check your histogram to make sure you’re not coming close to clipping the highlights. If you are, you’ll need to lower the ISO or exposure length.

Wooden Pier near Yellowknife, Canada, 15mm, f/2.8, 30 seconds, ISO 1600. (Photo by Grant Collier)

Stitching Images

The northern lights can fill up most of the sky, and even ultra-wide-angle lenses may only capture a portion of the display. To overcome this problem, you can create stitched images to capture more of the scene. A stitched image is one where you take multiple shots, each comprising a small part of the scene you want to photograph. You later use computer software, like Lightroom or Image Composite Editor (Windows only), to stitch these images together. The great thing about stitched images is that they will also produce larger images with more detail and less noise.

If the aurora is bright and moving fast, you’ll typically want to use a very wide lens, like 14mm, to create a single-row stitched panorama. You’ll have to take all of the images pretty quickly. Otherwise, the aurora can move so much that the images won’t stitch together seamlessly. If the aurora is relatively dim, it doesn’t tend to move as fast. In this situation, it’s possible to do multi-row stitched panoramas with up to 20 images. These large stitched images can help minimize noise, which is more noticeable when the aurora is fainter. I recommend a 24mm lens to capture such images.

Stacking Images

Another way to get more detail in an image of the northern lights is to stack multiple images. This is especially useful for getting more detail in the land if you shoot under no moon or a thin, crescent moon. I discuss stacking and stitching images in much more detail in the new, second edition of Collier’s Guide to Night Photography.

Vestrahorn Mountain, Iceland, 14mm, f/2.8, 10 seconds, ISO 1600. (Photo by Grant Collier)

When to Shoot the Aurora

The best time of the year to photograph the northern lights is near the spring and autumn equinoxes, in March and September. The northern lights tend to be somewhat more active during those months than others. Never plan a trip to photograph the northern lights between late April and early August. During this time, it isn’t dark for very long, if at all, at the far northern latitudes. If you plan a trip in December or January, it will be dark much of the day, if not all of the day. However, it can be bitterly cold during this time, so spring and autumn are still preferable for all but the most adventurous photographers.

Moon Phase

You can shoot the northern lights under almost any moon phase. The aurora will be brighter under no moon, but any foreground in your shot will likely be rendered as a dark silhouette. Under a full moon, the foreground will be well-illuminated and the aurora will be fainter, but this may not matter. The northern lights are often so bright that they will be easily visible under a full moon. My favorite time to shoot the northern lights is under a moon that is 20 to 50 percent illuminated. It will be dark enough to see the stars and aurora a little better than under a full moon, and you’ll still be able to render a lot of detail in the foreground. In order to be able to shoot under a variety of conditions, I recommend planning a trip so that you arrive near a new moon and leave near a full moon.

Avoid Lens Fog

Since it can be so cold when shooting the northern lights, your lens may fog up during the night. Lenses fog up much faster when they are taken from a warm location to a cold one. One way to prevent this is to keep your camera equipment cold by storing it in the trunk of your vehicle rather than in a warm room. You will, however, want to store your batteries in a warm location, as cold batteries will die faster. Another option to prevent a lens from fogging up is to attach hand warmers to the side of it using rubber bands to help keep it warm.

Lake near Yellowknife, Canada, 14mm, f/2.8, 15 seconds, ISO 2500. (Photo by Grant Collier)

Practice Near Home First

While there are ways to avoid lens fog, it is more difficult to avoid brain fog when shooting in frigid temperatures. Before paying for an expensive trip to see the northern lights, I recommend becoming proficient in night photography at locations closer to home. Photographing the northern lights is more difficult than photographing most other night scenes. The lights can move fast and may not appear for very long, so you need to be able to make the most of your time when the lights are out. If you practice with easier subjects beforehand, you should be able to come away with some great images.

For Further Training on Night Photography:

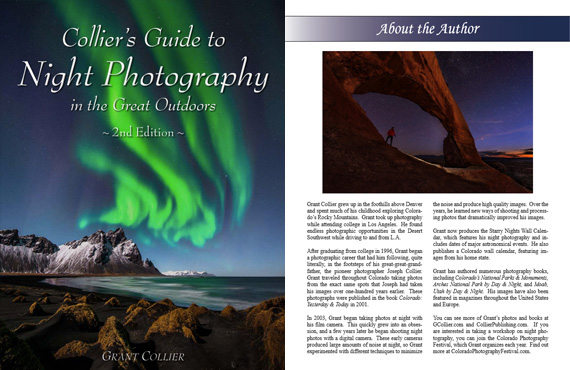

In this fully-updated 2nd edition, Grant Collier sheds light on how to capture these otherworldly images by sharing secrets he has learned over the past 17 years. He explains how to take photos of the Milky Way, northern lights, meteors, eclipses, lightning, and much more.

Our readers can get a discount by using the promo code picturecorrect at checkout which ends soon.

Found here: Night Photography Guide 2nd Edition

Go to full article: How to Photograph the Northern Lights

What are your thoughts on this article? Join the discussion on Facebook

PictureCorrect subscribers can also learn more today with our #1 bestseller: The Photography Tutorial eBook

The post How to Photograph the Northern Lights appeared first on PictureCorrect.

from PictureCorrect https://ift.tt/3ceD3E2

via IFTTT

0 kommenttia:

Lähetä kommentti